How’d you get from ecology and evolutionary biology to writing about science and science education?

I’ve been an academic my entire career. First I was a practicing scientist, then an administrator. My first permanent post-Ph.D. job was teaching biology at Oberlin College. As I became more aware of issues in the U.S., I began to feel that society didn’t understand or value the scientific method. I also saw this within the academy, and even in science courses at my institution – I had to unteach my students what they were learning in some other classes. They were taught that there were expected results, and that they should be able to explain why they didn’t get the “correct” results from an experiment. But science doesn’t mean you know the answers, science means you’re looking for answers. Science is a process, not a memorization of facts.

I also realized that outside the academy, it was even worse. People think that science is boring, difficult, and unnecessary. But we live in a participatory democracy, with many big decisions made by people who vote. And many of those decisions rest on a scientific basis, and if we don’t have a basic understanding of how science operates, we’ll make (and have made) some terrible decisions. So, I started writing about the methodology and philosophy of science for the public, usually in local op-ed pieces. That’s how it all began.

What led you toward The Clergy Letter Project?

The Reverend Judy Young at the March for Science in Washington, DC, 2017 (credit: Rev. J. Young).

Early on at Oberlin, during the Arkansas trial about teaching creationism in public schools, I received a note from the ACLU. They sent me some documents and asked if I would review the scientific content. Now, I hadn’t really been aware of the evolution-creationism controversy before, so I started reading about what was going on. I realized that one of the biggest attacks on science was coming from creationists. And, the documents the ACLU sent were all written by creationists. I’m an evolutionary biologist, and I understand the philosophy and mechanisms behind evolution, and I thought the documents were so harmful to kids’ education. I wrote a report saying so and sent it back to the ACLU (though it didn’t play any role in the outcome of the case).

I started reading more about creationism and writing about its challenges and dangers, first locally, and then a little more widely. I edited the newsletter of The Ohio Center for Science Education for a few years, but though I was correcting some of the most egregious misstatements made by creationists, they just continued misstating things. It made me feel like my work didn’t matter, so I stepped away from this work .

I then moved to Wisconsin as a dean at the University of Wisconsin, Oshkosh. Shortly after, I learned about Grantsburg, a small town where the school board was set to order that creationism be taught in its public schools. I was asked for help fighting that policy. I first wanted to write a letter to the school board and the local newspaper saying why the policy was damaging to students, but I realized that no one would care if it came from just me. So, I wrote it from the liberal arts deans in Wisconsin, all of whom I knew, and I circulated the letter among them. Almost all of them signed onto this letter explaining why the policy was dangerous and harmful to students, and we sent it in.

Then I was asked to do more. So, I drafted a similar joint letter from biology professors and religious studies professors, and I started circulating it through the UW System and getting signatures. Professors from private schools, including religious ones, saw it and signed on, too. Then I did a letter from anthropologists and one from geologists. The criticism of the letters became that college professors weren’t public school teachers. So, I drafted a letter for middle and high school teachers and circulated it to the Wisconsin Society of Science Teachers. I got hundreds of them to sign on, and sent that in to the local newspaper and to the Board of Education, too.

This all was useful, but not enough. I knew that if I wanted to have a real impact with the school board, I had to bring in local clergy. Being local, they have more credibility and sway, and when clergy start talking about science and how this policy contradicts their religious beliefs, people have to take more notice. So, a UCC minister drafted a letter which I circulated to Christian clergy, and I soon had 200 Wisconsin clergy members who signed this letter to the Grantsburg school board. Ultimately, the school board didn’t seem to care about the letters, but they began to get national and international media attention, and they backed down.

If I wanted to have a real impact with the school board, I had to bring in local clergy…. They have more credibility and sway, and when clergy start talking about science and how this policy contradicts their religious beliefs, people have to take more notice.

What came next?

I became aware of a court case in Dover, PA, what became the second-most important U.S. court case in the evolution-creation realm. The Dover school board was mandating that intelligent design be taught in public schools, and that a disclaimer about evolution be introduced in all public school science classrooms. Well, I had this wonderful Christian clergy letter that 200 Christian clergy members in Wisconsin had signed, and I thought, “If 200 people in Wisconsin were willing to sign on, I could get 200 clergy members in every state to sign that letter, present it to Dover, and really make a difference.” So, I started sending out this letter to Christian clergy in every state in the country, and people began to sign on. I thought I’d go public when I got 10,000 signatories.

I got there, but when I tried to go public, I couldn’t get the media interested! I decided at that point to try one last thing. I asked ministers to do something on the Sunday closest to Darwin’s birthday, to call it Evolution Sunday, and discuss the compatibility of science and religion – showing that these people who are saying evolution is anti-religion are not speaking for most religious leaders.

That first year, we had around 700 congregations across the U.S. participate and we got a fair bit of news reporting. I realized that we had the beginnings of a movement, and I called it The Clergy Letter Project. I kept thinking that when we achieved any given milestone, it would be over, but we just kept moving outward from there.

People who are saying evolution is anti-religion are not speaking for most religious leaders.

What was the focus of The Clergy Letter Project?

One, I wanted to demonstrate that there was nothing inherently anti-religious about evolution and there was no reason to be against it on religious grounds. Two, I wanted to demonstrate that the religious leaders who promoted creationism and attacked evolution may have been the loudest voices, but they weren’t the only voices. The whole group of religious leaders who thought differently deserved to be heard as well. Last, I wanted to show that you can have meaningful conversations about complex topics without shouting at each other.

And, many clergy who signed our letters wrote to me and said, “I thought I was alone. I believed in the compatibility of this aspect of science and religion, but I was nervous to say so because I didn’t know that others did too. Now I feel part of something bigger. Thank you.”

How did this expand beyond Christian clergy?

First, we expanded to Unitarian Universalist clergy, many of whom are Christian, but not all. This was in our third year, when Evolution Sunday opened up to people around the world and people from 20 different countries participated. That year was the 150th anniversary of the publication of On the Origin of the Species, and both NPR and Fox News ran stories about us, and they both were very positive! So I felt like we must be doing something right if we were getting both of those outlets to say good things about us, and about the compatibility of science and religion more generally.

Congregants at The Fountains United Methodist Church gather to celebrate Evolution Sunday (now called Religion and Science Weekend). (credit: Rev. D. Felton)

Around that time, a number of rabbis had seen the original Christian clergy letter, and they asked for a rabbi letter. So, a rabbi letter was drafted and plenty of rabbis signed on. But, they couldn’t participate in Evolution Sunday because they don’t celebrate on Sunday, so we changed Evolution Sunday to Evolution Weekend. That meant Jews could participate on Friday night and Saturday, and then some Muslims became interested as well.

We continued expanding over the next several years. We reached out to scientists to create a list of scientists who are willing to answer questions from clergy. Buddhists became aware of the project and interested in participating, so we had a Buddhist letter. Later, Humanists wanted to get on board, so then there was a Humanist letter too. We have one from Muslims written, too, and I’m trying to figure out the best way of circulating it so that imams will sign on, and then we’ll post the letter on the website. So, we now have a whole bunch of clergy letters from diverse faiths.

Many clergy who signed our letters wrote to me and said, “I thought I was alone. I believed in the compatibility of this aspect of science and religion, but I was nervous to say so because I didn’t know that others did too.”

What do you see in TCLP’s future?

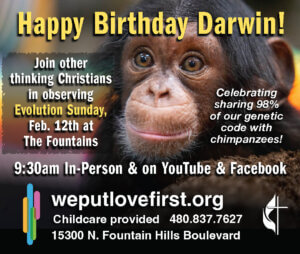

An ad from The Fountains, a United Methodist Church, for an Evolution Sunday (now called Religion and Science Weekend) event. (courtesy M. Zimmerman)

The clergy who’ve signed our letters have shown me that the connections between religion and science go further than just evolution. They encouraged me to have The Clergy Letter Project become a loud voice for taking serious action on climate change, and we now have a climate letter that clergy around the world have signed. We have taken positions and put out letters about other controversial issues that touch upon religion and science like racism and separating migrant children from their parents. We’ve moved beyond the creation-evolution issue to other issues in which religion and science can teach us something about public policy. This year, our members voted to rename Evolution Weekend, and now it is called Religion and Science Weekend, reflecting the broad range of issues that clergy members find compatible between religion and science.

I hope that The Clergy Letter Project can continue to be a voice of reason bringing religion and science together. I hope we can keep showcasing viewpoints that enable the creation of reasonable, rational public policy by bringing together seemingly divergent voices in a respectful way. I hope we will continue showing how to have respectful, meaningful dialogue about complex issues, and by doing that, move people towards better public policy. I hope that the public policies we support five years from now are rationally based in science and humanism, and are for the good of all humans and our environment.

What impact does putting out a letter have?

The evolution letters have been presented to school boards over the years, and usually, the boards that are considering teaching creationism back off. Correlation is not the same as causation, but there is enough evidence that the letters helped. Similarly, there have been people in congregations that have been moved to action by our climate letter addressed to business leaders and elected officials.

I also know that the clergy, as I mentioned before, feel like they’re part of a community with us, and that helps them. It may not change their entire life, but they feel a little more comfortable speaking about topics that they might not have spoken up on before.

Most importantly, I believe that the letters help us as a society to have meaningful conversations about complex topics rather than just shouting at each other with soundbites.

What values shape your approach to these issues?

Science as an endeavor is no more important than any other. If you care deeply about science, it doesn’t mean you shouldn’t care deeply about anything else (including religion), it just means you can’t ignore science. Also, there are some types of questions that science can’t touch. Once you recognize that there are areas outside of the realm of science, then you can say what the realm of science is, and you can explain why that’s important.

My roots are in the importance of education and the value of the liberal arts. And if you believe in that, you have to believe that there can be meaningful discussion among people who differ widely. We don’t have to believe the same things, but we do have to listen to each other and understand why we disagree.

How has science and faith discourse about evolution changed over the last decade?

The evolution-creationism controversy hasn’t been resolved, but it’s no longer central. There was this belief that there is a war between science and religion, but I’ve discovered that the war doesn’t exist as people thought. Yes, there can be some conflict between science and religion, but it’s not actually religion vs. science. One side is a small group of religious fundamentalists, and on the other side are many other religious leaders, and also scientists. But that narrow view of religion, fundamentalism, gets most of the public attention.

Also, the idea of compatibility between science and religion has taken on a slightly new form. The Clergy Letter Project going beyond evolution and creationism reflects what’s happening in society at large. People have begun to see that there are other issues where clergy can stick to their faith and still influence public policy.

Yes, there can be some conflict between science and religion, but it’s not actually religion vs. science. One side is a small group of religious fundamentalists, and on the other side are many other religious leaders, and also scientists. But that narrow view of religion, fundamentalism, gets most of the public attention.

Any suggestions for those interested in engaging with people of faith, but who don’t know where to start?

We often view the “other” as a monolithic block. We believe that when we see a terrible thing from someone in a group, that it’s true of everybody in that group, and that’s just wrong. No question that there are some religious leaders who are very anti-science, but the vast majority of them are not anti-science, which is what The Clergy Letter Project is all about. All religious leaders should not be characterized by the worst religious leader in the world.

People are individuals who have individual beliefs, and their individual beliefs so often are compatible with yours. You don’t have to share someone’s faith to talk with them respectfully, but you do have to respect them as a person and their beliefs. And remember that they may not believe what you think they do!

Second, whenever you reach out to somebody you don’t know well, remember that they have something to teach you, too. Maybe it’s something you know about, maybe it’s not. But if you have meaningful and engaged dialogue, you will learn as much as you give.

Third, reach out to people who disagree with you, learn from them, and work with them – but do it respectfully. If you do it in a condescending way, people aren’t going to listen. When you’re an evolutionary biologist involved with the creationism-evolution controversy, people come to you all the time and say, “You don’t really understand evolutionary biology. I understand it because I read about it. I don’t need to take classes; people with classes are just biased.” And it’s hard to respect that viewpoint because your knowledge base and everything you stand for is being undercut. So, why would you go to somebody and undercut everything they believe in and expect them to embrace you? Respect takes you so far, and respect really does mean listening as well as talking.